This paper describes work towards a scrutably adaptive teaching system. We outline our motivations for scrutability. Then we give an overview of Tutor3 and a report on a qualitative evaluation to assess whether users could understand the results of the adaptation and how to change their user model to control the adaptation. This report indicates that participants in the evaluation could, generally, understand how the material was adapted and how to control that adaptation. It also highlights some serious challenges for supporting scrutability.

Scrutable, user model, adaptive hypertext, adaptation control, adaptation visualization, adaptive web environment.

A scrutable adaptive system enables the user to delve into the way that the system has been adapted. We have several major motivations for this work: the first relates to issues of control over private information; the second is our belief that electronic teachers should be scrutable since they should be able to account for their actions in terms of the real drivers for adaptation and this maintains the position of the learner as the human who controls the machine; finally, there is the goal of improving learning. Key concerns to achieving these goals are how to best present the results of adaptation to the user in a way that they can understand what caused the adaptation and how they can control it.

While an accessible student model provides an excellent basis for reflection and for discussion, we would like to explore ways for the learner to see the implications of their student model in terms of the adaptations that it effectively controls. Essentially, we want to enable a learner of an adaptive system to be able ask `How was this material adapted to me?’, `How might this system teach this to someone else?’ and to be able to see just how their student model affected what they saw in the hypertext document. At this stage, the user model is quite simple. However, this makes a logical starting point for exploring ways to effectively provide support for users to scrutinise the adaptation of a system.

The design of Tutor3 was informed by our evaluation of its predecessors [4,5]. Tutor, the first version, was evaluated in a field trial. This appeared to be quite successful, with a total of 113 students registering with the system, 29% exploring the adaptivity and, of these, 27% checking what had been included as part of the adaptation and where content had been excluded. This evaluation identified limitations, too. While it did show material that had been adaptively included, it showed only the location of material excluded. Also, some users failed to appreciate that they could, affect the adaptation, at any time, by altering their answers to the profile questions. In essence, the Tutor evaluation showed promise but also identified ways that the scrutability support was incomplete.

These concerns were addressed in Tutor 2. We performed a qualitative evaluation to assess whether users could scrutinise its adaptation effectively. The student should be able to:

Determine what content was included/excluded on a page;

What caused the adaptation;

Understand how to change their profile to control what content is included/excluded.

The evaluation of Tutor2 indicated that users could not do these things. So, we completely redesigned the adaptation explanation to the form it has in Tutor3. We note that the whole purpose of a scrutable adaptive hypertext is to ensure that the student can, in practice, scrutinise it to understand and control the adaptation.

Section 2 gives an overview of the learner’s view of Tutor3. Section 3 describes the design of the evaluation study and Section 4 reports the results. The final section discusses these and conclusions.

Tutor3 is a web-based tutoring environment. The system employs the adaptive presentation technique of inserting and removing page fragments. For other adaptive presentation techniques the user is referred to [1.2]. The author creates lesson content in ATML, an XML syntax that adds simple mark-up to HTML. Mark-up is added to adaptive page fragments to describe the user model attribute/value pairs a user must hold to be shown that fragment within the lesson page. This approach is similar to the adaptive presentation technique used in AHA! (De Bra, 2002), although Tutor3 allows only simple boolean rules in the page fragment criteria. In this paper, we focus on aspects of Tutor3 related to scrutability. For other aspects, see [4,5].

The starting page gives an overview of Tutor3 and links to register and login. Once logged in, first time users see a welcome message explaining the need to answer some questions and that:

`The answers you give will be stored by the system, in what Tutor calls your profile, and will help Tutor customise each lesson to you. You will be able to review and change your profile at any time and, by doing so,alter how the material is customised to you. At the bottom of every lesson page, there is an explanation of how the lesson has been customised to you.'

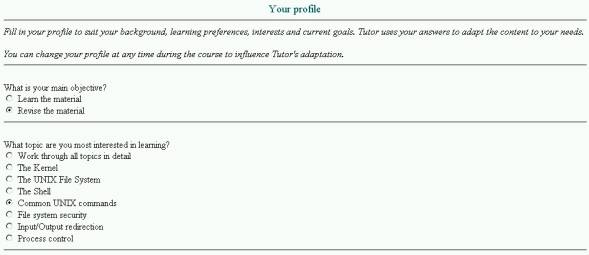

Each unit starts with a set of questions, as in Figure 1. These set the values in the student model. For example, the first question asks the student if their goal is to Learn the material or Revise the material.

Fig. 1. Example of a profile display. Tutor3 presents students with a set of questions and uses their answers to establish their student model (profile). This screen shot and later ones are all from Netscape 4.7.

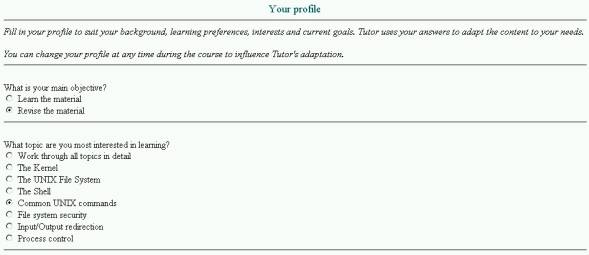

Next, Tutor3 presents lesson content as in Figure 2. The icons, near the top, link to various Tutor facilities. These include the course map, a page for the student to make notes, the glossary and on-line help. Importantly for this paper, the head accesses the profile. This enables the student to alter this at any time and so, to influence the adaptation.

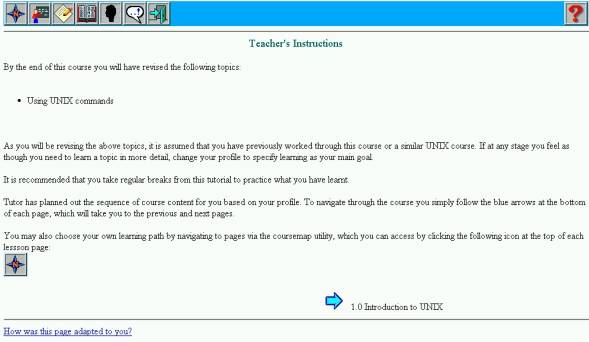

As the Figure 2 has adaptation, it has the link: How was this page adapted to you? Clicking this, a hidden section appears as in Figure 3 to explain the adaptation. On pages without adaptation, this link is replaced by the text: There was no adaptation on this page.

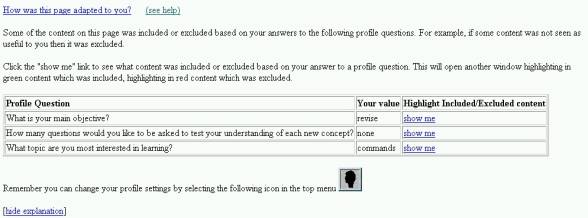

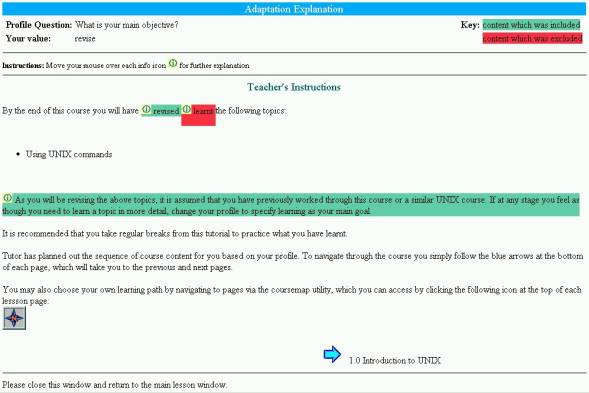

The adaptation explanation, as in Figure 3, shows each profile question that influenced adaptation of the current page. Beside the question is a short form of the student’s current answer, as in the student model, and a show me hyperlink. For example, the first row in Figure 3 indicates some adaptation was caused by the user answering revise to profile question What is your main objective? Clicking show me opens a separate browser page, the Adaptation Explanation, as in Figure 4.

Fig. 2. Example of an adapted lesson page. Clicking the hyperlink How was this page adapted to you? at the bottom of the page provides an explanation of adaptation that occurred on the page (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Example of an explanation section at the bottom of an adapted lesson page. This explanation is displayed by clicking the hyperlink How was this page adapted to you? from a lesson page (see Figure 2). Clicking the show me hyperlink opens a separate browser page showing content that was included or excluded (see Figure 4).

Content that was included has a green background, while excluded content has a red background. This is explained in the Key at the upper right. In Figure 4 the word revised in the first paragraph and the second paragraph beginning with As you will is highlighted in green, the word learnt in the first paragraph is highlighted in red. At this point, the student can see both the page in Figure 3 and that in Figure 4 in separate browser windows so they can compare the Adaptation Explanation against the original lesson page. In fact, since the Adaptation Explanation for each profile question is displayed in a separate browser window, the user can compare multiple adapted versions of the page.

An info icon is displayed within each highlighted section of content which was included or excluded. Moving the mouse over this icon pops up a further explanation. For example, in Figure 4, moving the mouse over the info icon in the first highlighted section, before the word revised, pops up the text This content is included if your value for the above profile question is revise.

Fig. 4. Example of an adaptation explanation page showing content that was included and excluded based on the student’s answer (revise) to the profile question What is your main objective?. Content that was included is highlighted in a green background colour (in the figure the word revised in the first paragraph and the second paragraph beginning with As you will is highlighted in green). Content that was excluded is highlighted in a red background colour (in the figure the word learnt in the first paragraph is highlighted in red). Moving the mouse over the info icon in a highlighted section pops up a further explanation. For example, moving the mouse over the info icon in the first highlighted section, before the word revised, pops up the text This content is included if your value for the above profile question is revise.

Our evaluation was qualitative, based on a think-aloud [9]. This has the merit of being relatively low cost and giving insights into the causes of difficulties. Following Neilsen, we selected five participants for the evaluation. There have different backgrounds and varying degrees of computer literacy: one was a secondary school student, two were third year computer science degree students and there were two adult participants with basic computer literacy skills.

We designed the evaluation around a fictitious person, Fred. This meant that all participants were dealing with the same student profile and we could predict the exact adaptation each should see. This, in turn, meant that all participants did exactly the same task and saw exactly the same screens.

Each participant was provided with a worksheet. This described Fred’s learning goals, interests and background. Participants were asked to assume the role and background of Fred and use Tutor3 to start working through the beginning of the Introductory UNIX course. Participants were presented with one page of the worksheet at a time so they could not jump ahead.

The tasks of the worksheet were designed so that each basic issue was explored in three subtasks. This provided internal consistency checks, an important concern since there are degrees of understanding and we wanted insight into just how well each participant was able to scrutinise the adaptation. Extracted questions from the worksheet are shown in Table 1. The worksheet asked the participants to:

Explain the use and effect of a Fred’s answers to profile questions;

Explain how Tutor3 decides what content is included/excluded on a page;

Demonstrate control over adaptation by changing answers to profile questions.

Table 1. A sample of questions in a worksheet completed by participants in the evaluation of Tutor3.

|

Concept |

Questions presented in worksheet |

|

Explain the use and effect of Fred’s answers to profile questions |

|

|

Explaining how Tutor3 decides what content is included/excluded on a page |

|

|

Demonstrating control over adaptation by changing answers to profile questions |

|

The first part of the worksheet instructed the user to register with the system, log on and select the Introductory UNIX course. The first task was to complete the profile of Fred (as in Figure 1). The worksheet did not specify the answers for each question but did describe Fred’s learning goals, interests and background. Each participant was asked questions from the first block in Table 1.

The second part of the worksheet asked each participant to navigate to a specific page, that shown in Figure 2. Then, participants were asked to determine whether any of the content on that page was adapted to Fred, based on the answer to the profile question What is your main objective? The participant had to indicate any adapted content and whether it was included or excluded. To perform this task, the user had to notice and click the hyperlink How was this page adapted to you?

The third part of the worksheet involved what-if experiments. The participant was asked to guess the content of a specific paragraph, assuming Fred were to change his answer for the profile question What is your main objective? to Revise the material. Answering this question should not have required any guesswork. The answer is on Adaptation Explanation as in Figure 4.

Table 2 summarises the results of the evaluation. It shows the range of age, academic background and computer literacy. Overall, they represent a quite computer literature group.

The fourth row of Table 2 summarises the participants’ understanding of the core concept that answers given in the profile were used to adapt the content. They first had to answer the 8 profile questions, as Fred would have. These appeared as in Figure 1, with additional questions about preferences for abstract explanations, numbers of examples and self-test questions, interest in historical background and understanding of other operating systems. For this experiment, the critical aspects about Fred’s background were that he wanted to learn (not revise) and he was not interested in historical background information. All participants answered these profiles questions consistently with the information we provided about Fred.

All participants understood that profile answers controlled the adaptation. However, Participant 4 believed they would not be able to influence or control the way Tutor adapts content. Participant 3 believed they might have the ability to do so but did not understand how. Participant 5 initially did not appreciate that profile answers could be changed later. Overall, at this stage, having just completed the profile, participants understood that profile answers affected adaptation, but did not know whether they would be able to control the adaptation. Note that this is inspite of the message at the top of the screen (see Figure 1):

‘Fill in your profile to suit your background, learning preferences, interests and current goals. Tutor uses your answers to adapt the content to your need.

You can change your profile at any time during the course to influence Tutor's adaptation.'

Table 2. Summary of qualitative evaluation of Tutor3.

|

|

Participant 1 |

Participant 2 |

Participant 3 |

Participant 4 |

Participant 5 |

|

Age group |

21-25 |

21-25 |

18-21 |

18-21 |

14-18 |

|

Background |

Post study adult |

Post study adult |

Year 3 Comp Sci degree student |

Year 3 Comp Sci degree student |

Secondary school student |

|

Computer literacy |

Basic |

Basic |

High |

High |

Moderate |

|

Understood role of the Profile |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Understood green background shows adaptively included content |

Partly – and needed help to access explanation |

Yes but needed help to access explanation |

Learnt this concept through the evaluation |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Understood red background shows adaptively excluded content |

Partly – and needed help to access explanation |

Yes but needed help to access explanation |

Learnt this concept through the evaluation |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Understood profile answers may be changed to alter adaptation of content |

No – did not know how to access profile |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Time to complete worksheet |

50 min |

31 min |

20 min |

22 min |

28 min |

The fifth row shows how well the participants understood the Adaptation Explanation of the text included, based on their written responses and actions performed to answer the middle three questions in Table 1. This required that they appreciate that the green background indicated adapted content had been included, because of the answers to the questions on the Profile Page. Participants 1 and 2 needed help in accessing the explanation in order to continue the worksheet. Allowing for this, all participants other than Participant 3 did understand that the green background indicated content that had been included. Participant 1 stated that they did not understand why the other (non-adapted) content was not also given a green background. Participant 3 did not notice the highlighting feature when completing this stage of the worksheet. This participants’ method for determining whether content had been adapted was to go back to the profile page, change their answer, navigate back to the lesson page and study the content for changes. This participant correctly identified the included content. Later, Participant 3 discovered the highlighting feature and showed understanding of the concept.

The next row shows the participants’ understanding of the Adaptation Explanation for material that was excluded. It shows exactly the same pattern as for included material. One exception occurred with Participant 3, who could not identify excluded content through their un-aided visual approach to determining whether content was excluded.

The second last row shows the participant’s understanding of the central notion that they could alter the adaptation by altering their answers to the profile. The worksheet asked participants to alter the adaptation on a page (see last three questions in Table 1). The first question asked the participant to determine the content of a page assuming a specific profile setting, without actually changing the profile. To answer this question, we expected the participant would examine the adaptation explanation which shows how the content would be affected based on a change to the profile. Participant 3, who had not yet discovered the adaptation explanation, was not able to determine the expected page content. Participant 4 had previously demonstrated an understanding of the adaptation explanation but did not realise that the facility could be used to predict the content of the page in this case. The final question in this section asked participants to change their profile to see if their expectation of how the page would appear was correct. This would demonstrate the ability to change the profile to achieve a desired effect on adaptation. All participants were able to change their profile as required, except Participant 1, who could not work out how to access the profile.

The final row shows the time taken for the full experiment. Participant 1 took about twice as long as most of the other participants, who took 20 to 31 minutes. Since this included the time to complete the worksheet and to think-aloud, it is not indicative of the time needed to explore the way material is adapted.

Overall, Participants 2, 4 and 5 understood how to interpret the adaptation explanations and were able to use the explanations to control the inclusion/exclusion of content to a desired effect. Participant 1 understood the adaptation explanation but could not work out how to change the adaptation. Participant 3 did not discover the adaptation explanation until late in the evaluation but then demonstrated understanding of it.

A key concern, highlighted by the experiment, was that users had great difficulty finding the adaptation explanation. Participants 1, 2 and 3 required help to find the link How was this page adapted to you? Participant 4 found this link without help. Due to a browser anomaly, Participant 5 was presented with the adaptation explanation without the user having to click the link.

The purpose of a scrutable adaptive hypertext is to ensure that the user can scrutinise it to visualize, understand and control the adaptation. This paper has described the Tutor3 system. It complements previous work on open user models, by taking the next step, and supporting openness of the process of adaptation to present the results of adaptation and a way of altering the adaptation. From the user’s point of view, Tutor3 enables them to thoroughly explore the implications of the user model.

At this stage, Tutor3 has an extremely simple student model. It is entirely defined by the student’s answers to the questions on a profile page. That page is presented at the beginning of each login to Tutor. It is also available from every Tutor page. On the one hand, this is a weakness, since the processes for constructing the student model are so restricted. However, at this stage, this simple model makes a logical starting point for exploring ways to effective support for users to scrutinise the adaptation of a system. It seems unwise to proceed to more complex underlying student models until we can demonstrate that we can support scrutable adaptivity in relation to an intuitive and simple underlying student modelling process.

We have reported a small, qualitative evaluation of the scrutability support. Our most striking finding is that it is quite difficult to support scrutability. This may be, in part, because the notion is new. Tutor3’s scrutability support appears to be quite good, with some reservations. It seems that users need help in getting started. A simple tutorial session should help. Of course, this will only help if students do it! At the same time, our evaluation indicates that once students make their way to the Adaptation Evaluation page, they can understand how to scrutinise the core adaptation elements: the role of the profile, the material that has been included/excluded, what caused that adaptation and how to alter it.

Brusilovsky, P. (1996). Methods and Techniques of Adaptive Hypermedia. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, Vol. 6, n 2-3, pp. 87-129, Kluwer academic publishers.

Brusilovsky, P. (2001). Adaptive Hypermedia. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, Vol. 11, n 1-2, pp. 87-110, Kluwer academic publishers.

Bull, S. P Brna, H Pain (1995). Extending the scope of the student model, User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 5(1), 44-65.

Czarkowski, M and J Kay, (2000) Bringing scrutability to adaptive hypertext teaching, ITS'2000, Intelligent Tutoring Systems, Gauthier, G, C Frasson, K VanLehn (eds), Intelligent Tutoring Systems, Springer, 423--432.

Czarkowski, M and Kay, (2002) A scrutable adaptive hypertext, De Bra, P, P Brusilovsky, R Conejo (eds), Proceedings of AH'2002, Adaptive Hypertext 2002, Springer, 384 - 387.

De Bra, P., Aerts, A., Smits, D., Stash, N. (2002). AHA! Version 2.0, More Adaptation Flexibility for Authors. Proceedings of the AACE ELearn'2002 conference, October 2002, pp. 240-246.

Dimitrova, V., Self, J.A. and Brna, P. (1999). The interactive maintenance of open learner models, International Conference on AIED, Le Mans, France, 1999, 405-412.

Kay, J. (1995). The um toolkit for cooperative user modelling, User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 4(3), 149-196.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Estimating the number of subjects needed for a thinking aloud test, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 41(1-6), 385-397.

Self, J.A. (1990). Bypassing the intractable problem of student modelling, in C. Frasson and G. Gauthier (eds.), Intelligent Tutoring Systems: at the Crossroads of Artificial Intelligence and Education, Ablex, Norwood, N.J., 107-123.

Self, J.A. (1999). Open sesame?: fifteen variations on the theme of openness in learning environments, International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 10, 1020-1029.